Cleaning out the basement

As it happens, my last efforts to put some order in our basement coincided with the 70th anniversary of the uprising of 17 June 1953. Even though I was not yet born at that time, I associate many memories with the anniversary of this historic event in the early days of the German Democratic Republic, and with the street, where the uprising started.

A painter and his painting

While rummaging in one of the back corners of the cellar, I found a reproduction of the painting “Baustelle Weberwiese” by the little-known painter Lothar Howald. The painting with its dark wooden frame was a birthday present during our time in Dresden, in the late 1990s, more than 45 years after the uprising. It first hung in my office in Löbauer Straße, then in Zittauer Straße. The picture shows a meeting of architects and construction workers, among them – in the spirit of socialist realism- also some women, in front of scaffolding and growing buildings on the Weberwiese.

It was also in Dresden, where the painting was exhibited for the first time, at the Third German Art Exhibition from 1 March to 25 May 1953. On 12 March 1952, the German weekly newspaper Die Zeit published an article on the subject on 12 March entitled “Painter Brigades Provide Optimism”.

A example of Socialist Realism

“In formal terms, this painting amounts to idealising naturalism. As precisely as each badge and each machine model should be recognisable, the overall impression must be ‘unrealistic’: namely, victorious and optimistic in any case. After all, anyone looking at such a picture is supposed to be filled with “courage, confidence and enthusiasm” for the goals of the SED, for the Five-Year Plan and the “defence of progress”.

The painter Lothar Howald and his painting are largely forgotten today. On the internet, there are still picture postcards with a reproduction in black and white on offer, at a price of 8.99 EUR. My attempts to sell the painting on various classified ad portals have so far failed due to lack of demand.

The construction site

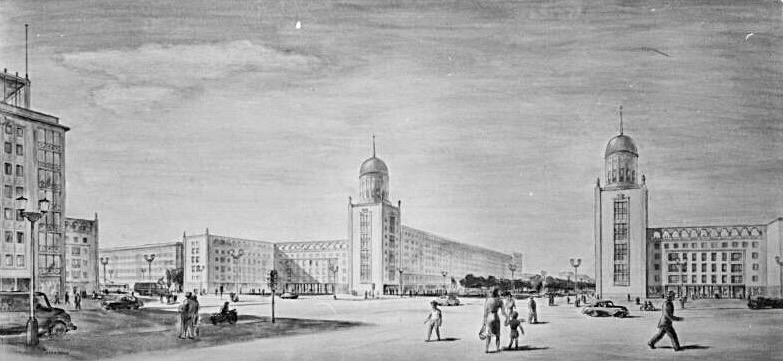

The former “Große Frankfurter Straße“, the main street and arterial road to the Hanseatic city of Frankfurt an der Oder, was given the name “Stalinallee” on 21 December 1949, shortly after the founding of the GDR on 7 October 1949, as a birthday present to the Soviet dictator. Stalinallee was the first “socialist street” in the still young GDR. The street, which had been badly bombed in World War II, was to be rebuilt with a new urban planning and architectural concept. A shining example of socialist architecture was to be built in the centre of Berlin, based above all on the Soviet model. After an urban planning competition, construction began in 1951 under the direction of Hermann Henselmann.

Despite a massive shortage of materials, the 2.3-kilometre-long Stalinallee was the largest construction site in the GDR. The work was under great time pressure. Therefore, workers, machines and building materials were gathered from all over the Republic, to the annoyance of the residents of the rest of the GDR. With an appeal in the daily newspaper Neues Deutschland, workers were sought for the “National Reconstruction Programme Berlin”.

As early as 21 December 1952, there was a ceremonial handover of keys for more than 1,000 flats, and in January 1953 the first 70 flats were occupied. About two-thirds of the living space was given to rubble women, construction workers and reconstruction helpers, the rest went to white-collar workers and academics.

The flats in Stalinallee were pure luxury at the time: unlike the holes in the tenement blocks, they were not only large and bright, but had lifts, district heating, hot water supply, built-in cupboards, tiled bathrooms and rubbish chutes. Some also had telephone connections and parquet flooring, and there were terraces on the roofs for the general use of the tenants.

The uprising

Even before the first foundations had been dug, the GDR honoured the street’s namesake: on 3 August 1951, a 4.80-metre statue of Josef Stalin was ceremoniously unveiled. When the dictator died on 5 March 1953, there was the first large demonstration in Stalinallee, tens of thousands of people marched to the monument to condole with the deceased dictator.

Only a quarter of a year later, on 16 and 17 June, the construction workers of Stalinallee demonstrated against an increase in standards that had been decided shortly before. This demanded that workers work 10 per cent more, but without receiving more pay in return. The construction workers’ protest against this unpaid extra work at the Stalinallee construction site turned into an uprising that quickly spread to almost all cities and districts in the GDR.

In the East: Knocking off Stalin from his pedestal

After its suppression, this first mass uprising in the Soviet Union’s sphere of rule after the end of World War II, was always understood in the GDR and the Soviet Union as a “fascist coup attempt”.

After the official renunciation of Stalin worship at the 22nd Party Congress of the CPSU in October 1961, all cities, mountains, institutions and enterprises, streets and squares in the Soviet Union named after Stalin were given new names. Just two weeks later, on 14 November 1961, the GDR also renamed Stalinallee as Karl-Marx-Allee. At the same time as the street was renamed, soldiers of the National People’s Army knocked the Stalin statue off its pedestal in a night and fog operation.

In the West: A public holiday in summer

In the West, the Berlin Senate decided as early as 22 June 1953, only a few days after the uprising, to rename the Charlottenburger Chaussee, which runs from the Brandenburg Gate through the Tiergarten to Charlottenburg, as the Street of 17 June. in the Federal Republic of Germany, 17 June was declared a public holiday on 4 August 1953.

Ten years later, on 11 June 1963, almost two years after the Berlin Wall was built, the then Federal President Heinrich Lübke proclaimed 17 June a “national day of remembrance”. After the fall of the Wall and the restoration of German unity, 3 October was declared “German Unity Day”. The law of 4 August 1953 was repealed, but the Federal President’s proclamation of 11 June 1963 is still valid.

In my youth, but also later, this holiday in June was always something like the beginning of the summer holiday season. The historical occasion increasingly faded into the background.

In the summer of 1961 I missed the 17 June holiday in Germany, because I was with my parents in Vienna. This year, I waved to Khruchov and Kennedy as they drove past Schwarzenbergplatz in an open convertible during their meeting on 3 and 4 June. Khruchov later laid a wreath there at the Red Army Monument.

There is a street in Berlin…

In 1969, the singer-songwriter Wolf Biermann dedicated a song to the street with the title “Eight arguments for keeping the name Stalinallee for Stalinallee“.

Und Henselmann kriegte Haue, damit er die Straße baut. Und weil er sie dann gebaut hat, hat man ihn wieder verhaut.

And Henselmann got a beating so that he would build the street. And because he built it, they beat him up again.

However, the song was only released in 1972 on the long-playing record “Warte nicht auf bessre Zeiten” (“Don’t wait for better times”), which was only released in the West. The LP with the cover photo of Biermann’s flat in Chausseestraße was one of the first records I bought after I finally had a record player.

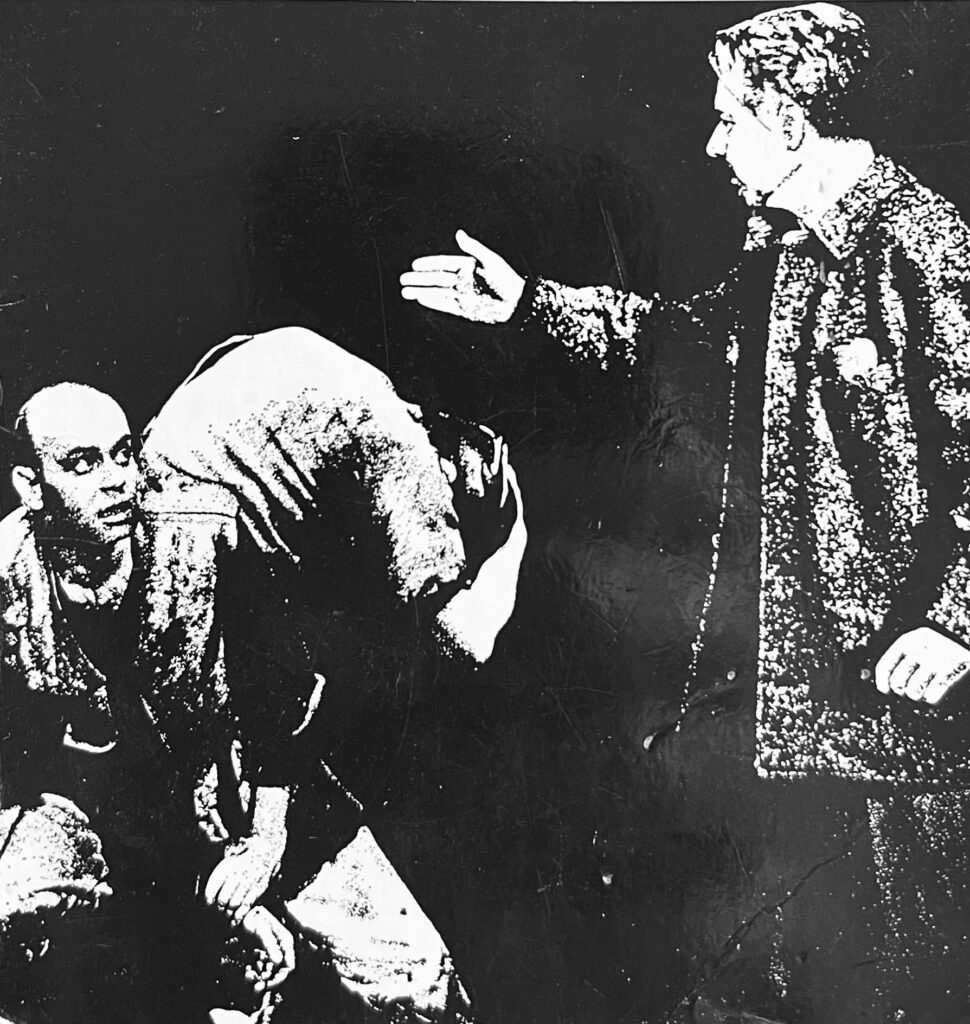

The Plebeians Rehearse the Uprising

In my school’s theatre group, I took part in the performance of Günter Grass’ play “Die Plebejer rehearse den Aufstand” (The Plebeians Rehearse the Uprising) around the same time. First performed in 1966, the play caused a major scandal because it denounced Bertolt Brecht’s behaviour towards the uprising on 17 June 1953.

The Karl Marx Bookshop on Karl Marx Allee

In the 1970s, during frequent visits to Berlin, the Karl Marx Bookshop was always a destination on day trips from the west to the east part of the city.With the money from the compulsory exchange of I bought here the three volumes of Das Kapital, some other volumes of the blue complete edition of the works of Marx and Engels, as well as many other books and novels from Aufbau-Verlag.

Modern times

Today, Karl-Marx-Allee and Frankfurter Allee are popular residential areas, much sought after by tenants, but also by speculators. I often drive through this ensemble on my way to Berlin-Mitte or to the north of the city.

The street as an ensemble as well as many individual buildings are listed. The residential buildings in the avenue were bought by various investors after German reunification and often extensively renovated.

However, many of the commercial pavilions and shops, which are also listed, stand empty and suffer from the general crisis of trade and commerce in the city centres.